When Marie Antoinette and Madame X Shocked Paris

The fear of the female body

Two images, two centuries, the same city. In 1783, at the Paris Salon, a portrait of the Queen of France caused a scandal: Marie Antoinette posed in a white muslin dress, light as an undergarment.

In 1884, still at the Salon, another woman – Virginie Amélie Gautreau, a banker’s wife – provoked the same unease. The strap of her black dress slipped slightly from her shoulder, and bourgeois Paris recoiled in shock, just as it had a century before.

Fashion changes, reactions don’t. What do these two scandals tell us?

The female body, more than power or politics, has always been the ground on which society measures its idea of decency.

The chemise that shook the monarchy

In 1783, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun exhibited at the Salon her portrait of Marie Antoinette en chemise à la reine.

The dress, made of light muslin, was inspired by the “natural” gowns the queen wore at Trianon, far from court ceremony. But that simplicity, innocent in private gardens, became explosive in public.

In France, silk was a matter of national pride and economy, rooted in the policies of the Sun King; for the queen to favour light Indian muslin over heavy Lyon silk touched a sensitive chord of politics and prestige.

Moreover, the queen was a foreigner (an Autrichienne, as her detractors used to call her), which made her even more suspect of foreign sympathies.

The chemise was not a dress of state: it was underwear transformed by fashion’s whim. Marie Antoinette appeared too human, too close. Dressed this way, the queen lost her royal dignity.

The portrait was quickly withdrawn and replaced with a new one, featuring a blue silk dress more befitting the majesty of France.

But the damage was done: the image of the sovereign playing shepherdess only provided fresh ammunition to the pamphleteers and clandestine chroniclers attacking the Ancien Régime.

To many eyes, the light fabric, symbol of personal freedom, became the symbol of a queen’s frivolity and a monarchy in decline.

A century before photography, the power of public image could already destabilize a throne.

Madame X and the panic of respectability

A century later, the portrait of another foreigner in Paris scandalized the Salon.

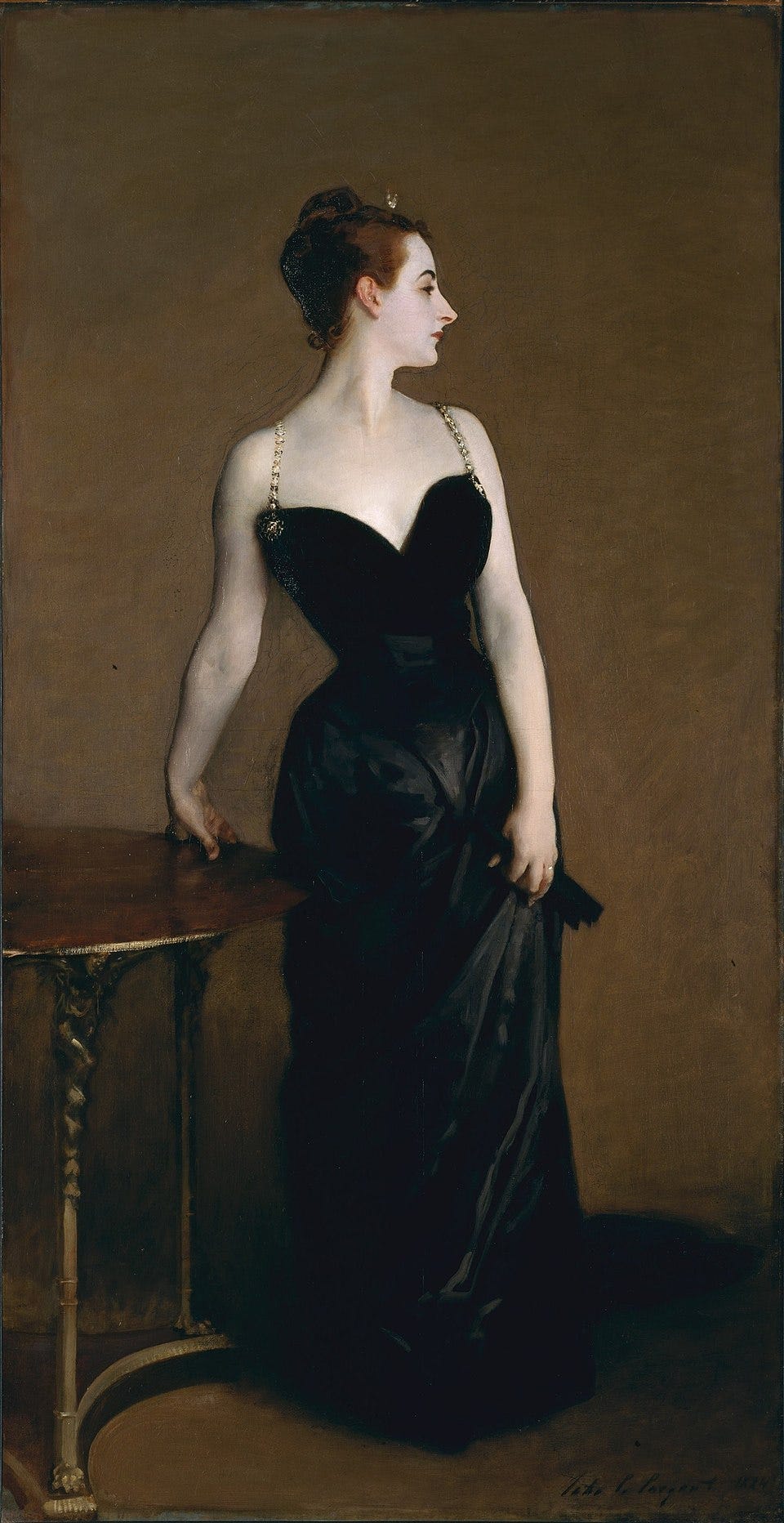

In 1884, John Singer Sargent presented his “Portrait de Mme ***”. Caution suggested he not name his subject, but it was a secret for no one: she was Virginie Amélie Gautreau, an American socialite married to a wealthy French banker.

Her dress was a masterpiece of tailoring, with black satin wrapping her form, a sharp neckline, and a cinched waist. The contrast heightened Amélie’s diaphanous skin.

But a strap, whether accidentally or deliberately slipped down her right arm and painted as such, unleashed scandal.

It was not the skin itself that offended: it was the dissonance between official, quintessential Parisian elegance and the implicit eroticism of that casual detail.

Late-nineteenth-century Paris had codified respectability as an aesthetic; deviation, even minimal, was read as social transgression.

Under pressure, Sargent repainted the strap in its proper place and later fled to England. Madame Gautreau became a social pariah.

Today, the painting is considered one of the great portraits of modernity: a portrait in which a woman begins to appear not just as an object of representation, but as a presence with her own agency.

The language of transgression

Both works told the same paradox: when a woman showed herself too honestly, society responded with moral panic.

In 1783, the chemise rejected ceremonial rigidity and proposed an idea of Rousseauian authenticity.

In 1884, Madame X’s black dress challenged bourgeois morality with calculated sensuality.

Two opposing aesthetics – natural and sophisticated – were guilty of the same symbolic “crime”: the autonomy of a woman’s body. In both cases, the dress became a shifting limit between public and private.

The scandal lay not in the body itself, but in the language of the fabric that clothed it. Marie Antoinette’s muslin stripped away distance from the sovereign; Madame X’s satin granted power to a woman who asked no permission.

A century of evolution and the same fear: that dress might stop representing society and start representing the person.

The echo of scandal

Marie Antoinette scandalized because she seemed to forget her rank, Madame X because she claimed a new one.

In both cases, fashion acted as a detonator: a different dress was enough to shake a system of values.

Today, the power of these two rejected portraits lies in showing us that every era has its own idea of “nakedness,” and that the threshold of tolerance is always a social fact before an aesthetic one.

Perhaps, rather than a century of progress, a thread of continuity ran between the two paintings: society’s difficulty in tolerating a woman who showed herself according to her own rules.

And perhaps it was there, in that rebellious strap and that light muslin, where modernity was born.

Thanks for reading!

You may also enjoy